Telling the history of Claremore…one story at a time BOB CHAMBERS HAS DEVOTED LIFE TO CHEROKEE HISTORY

BY: Ken Willhoite This article was published in the Claremore Progress June 27, 1993

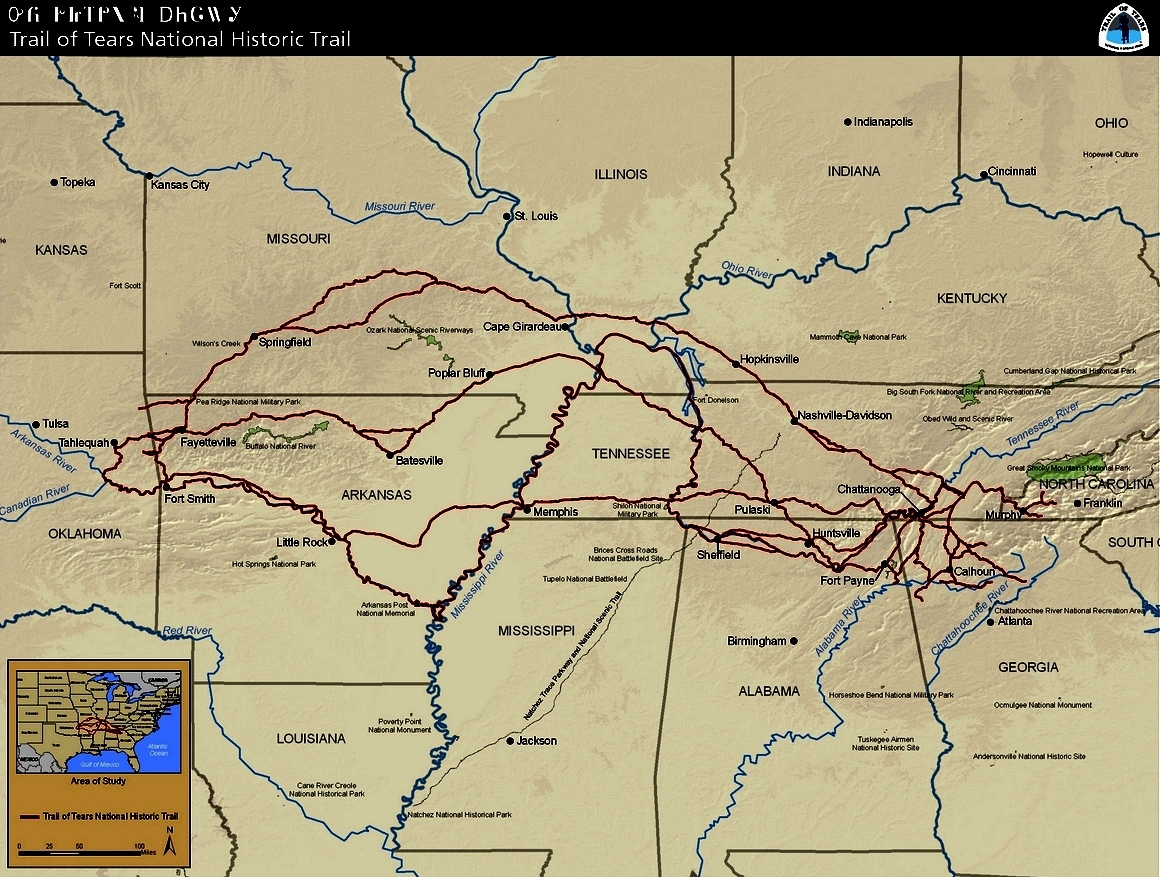

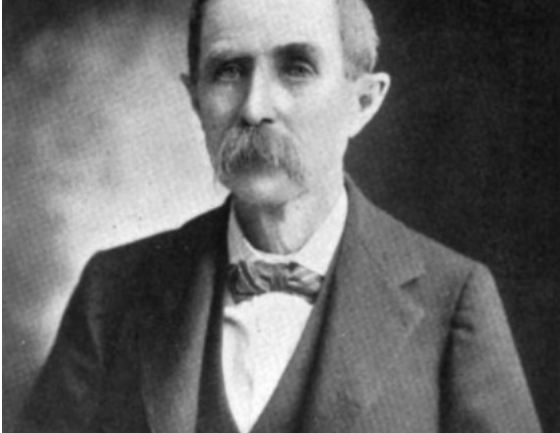

The influence of the American Indian is an undeniable part of the life and landscape of Rogers County. It is reflected in the names of its towns, the name of its streets and the mosaic of Indian allotments that make up its map. Somehow the influence seems ethereal, like ghosts from the past, forgotten in the busy hustle and bustle of the present. But, Bob Chambers of Claremore is diligently working to change that. He has devoted much of his adult life to tracing the history of the Cherokee people, the history of his family and Rogers County. He sits at a desk in the den of his Claremore home bathed in the warm light of a lamp that illuminates the work area in the otherwise dark room. Handwritten notes with family names and dates are scattered about the desk, and around him are shelves filled with research books and binders full of old documents that would make a research librarian’s heart flutter with envy. He rises out of his chair and goes to a corner to pull a chart of his family tree from its home on the shelf. The tree starts with the names of Bob and his brother and sisters at the trunk, branching upward and outward with a thick foliage of the names of those long since gone. The branches weave from name to name, interspersed with notations that to the non-historian may as well be Egyptian hieroglyphics. The upper-most branches run off the top of the chart as far back as the 1500s, linking the Chambers family by blood to at least 135 Rogers County families, including the family of Will Rogers. Perched near the uppermost left-hand branches of the tree is the name of Maxwell Chambers, Bob’s great-great-grandfather, and the one who first brought the Chambers to what would one day become Oklahoma. Maxwell Chambers was born October 20, 1793 to parents of Irish decent. As a young man, he married Elsie Sanders, who was half Cherokee. They made their home in a portion of Georgia which at that time was the Eastern Cherokee Nation. The couple worked the land and had eight children. Their lives were to be changed forever when, in 1838, the federal government removed the Cherokee people west on the infamous Trail of Tears. The great-great-grandson of Maxwell Chambers turns his chair toward the burgeoning shelves and pulls a bound stack of documents from its resting place. Flipping through the space provided for the leaders of 13 of the “detachments” that were rounded up to embark on the brutal journey. Columns on the document list the amounts of meat, bread, sugar, coffee and salt allotted to each. Two other columns contain the number of those who departed, and the number of those still alive at the trail’s end in Tahlequah. Maxwell Chambers’ detachment departed in October 1838 and arrived in February, many succumbing to the horrendous conditions of the trek. Maxwell, Elsie and their children managed to survive, promptly settling down in the Tahlequah area. The oldest Chambers boy, John, born in 1817, grew restless, and 11 months after the Trail of Tears, moved north and east to settle on pristine land near the Verdigris River. The rest of the Chambers children soon joined him, establishing home places stretching several miles from just south of what is now Claremore, to the river. “There was such a big bunch of people there (in Tahlequah) that they just decided to move out,” Bob Chambers said. “This area was close to the river, just like traditional Indian camps. That’s where the navigation and the hunting were.” Joseph Chambers married Nancy Jane Starr and built a store three-and-a half miles south of Claremore on the Butterfield stageline that ran from Chetopa, Kansas, to Stroud. A settlement known as Ponlas sprouted up around the store which contained the only post office between Big Cabin in the north and the future site of Tulsa to the southwest. A historical plaque off of S. Muskogee Avenue sits a quarter mile west of the “Old Ponlas.” The old Chambers cemetery, grown up with trees that weren’t even acorns when its inhabitants were buried, is the only remnant of the settlement. Joseph and Nancy had six children, including Teesey, in 1855, and William, in 1859. William, who was Bob Chambers’ grandfather, married Nannie Elizabeth Carey. William and Teesey took over the family store and, when the Frisco Railroad came through this portion of Indian Territory in the early 1880s, built the first two-story building for miles around directly across the road from the depot. The building, located at the former sight of Nabatac Bait Shop, became Claremore’s first store and post office…the seed that was to grow into a town. While running the store, William and Nannie Chambers had three sons, including Teece in 1895, who was Bob Chambers’ father. A few years later, in 1902, the federal government began doling out parcels of land to those of Indian descent. The Chambers family received allotments that are now within Claremore’s city limits, including areas surrounding Ne-Mar Shopping Center, Price Mart, the Rogers County Court House, and Radium Town. Bob has a 100-year-old map of the original Indian allotments in Rogers County. It covered half a wall in his den. His father’s allotment borders that of his uncle…the well-known Blue Starr, namesake of the Claremore road. Bob remembers his uncle as a big, jovial man popular throughout town. “Everyone loved him,” he said. “He was a true gentleman and quite a good mixer.” While Bob recalls his uncle fondly, it was his grandmother, Nannie, who first sparked his interest in Cherokee history. An intelligent woman, she was a Cherokee interpreter in local and district courts. “I was 11 when I first became interested,” Bob said. “It was through her that my interest grew. I inherited it from her.” After Bob grew up, he married Raye Belle Jacobs of Claremore. The couple moved around from state to state following Bob’s job as a crane operator. And, although Raye has passed away, a photograph high on her husband’s desk keeps her close at hand. “She watches over me,” he said. “She was one heck of a gal.” He pulls another book from its shelf…”History of the Cherokee Indians.” Published in 1921, it was written by the famous historian Emmet Starr, who happens to be Bob’s third cousin. It chronicles the bloodlines of thousands of Indian descendants. On another shelf is a stack of the historian’s notes containing staggering amounts of information on Cherokee families, including the Chambers family. The notes went unpublished after Starr’s death in 1930. Bob Chambers intends on keeping that history alive, bringing them up to date with every name of every person born of Cherokee descent. But he doesn’t dwell on why he does what he does. There’s no discussion of knowing your family’s past so you can know yourself, no advice on studying history lest you be doomed to repeat it. “I don’t know what it is that makes me like it,” he said. “What makes a drunk like whiskey? It’s just in his makeup like this is in mine.” Whatever the reason, Bob Chambers isn’t just documenting the history of the Cherokee people, the history of Claremore, and the history of the Chambers family. He’s making a valuable contribution of his own. (Bob died in 1996.)