Telling Claremore’s history…one day at a time

by Christa Rice in Explore Claremore’s History.

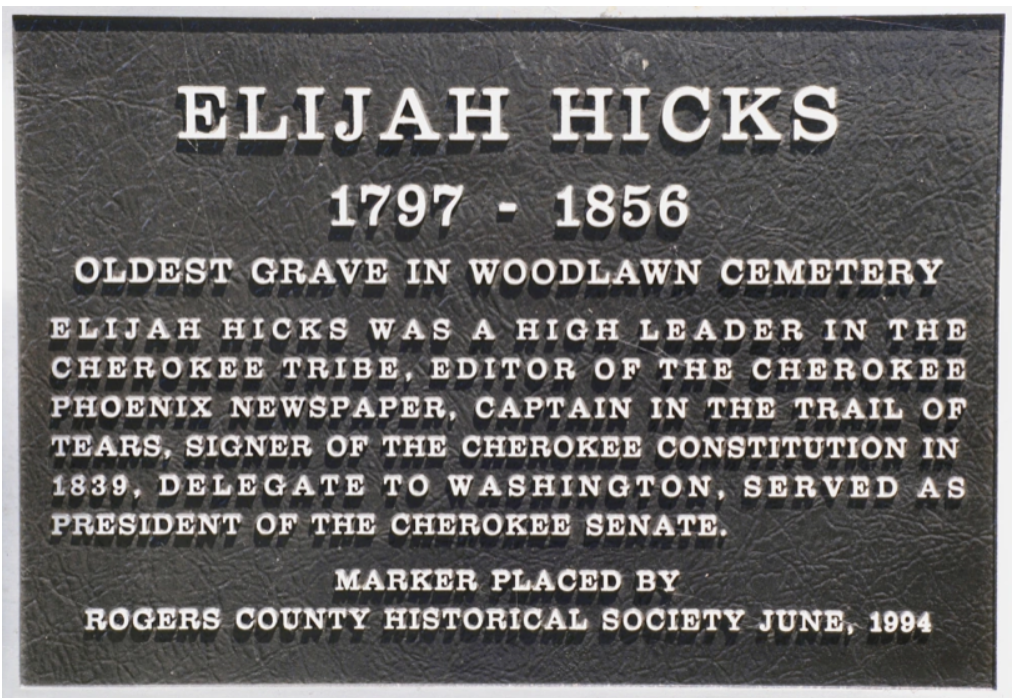

Walking through Claremore’s Woodlawn Cemetery on a peaceful summer’s day one comes upon a historic marker signifying the graveyard’s oldest burial site, the final resting place of one of Claremore’s earliest residents. This noteworthy Cherokee lived during a time of great Native American transition and hardship, of conflict with the United States over Cherokee sovereignty and dominion, a time that generated brilliant Cherokee Nation leaders such as John Ross, Sequoyah, and Major Ridge. Elijah Hicks, statesman, diplomat, and peacemaker was one whose honorable character strengthened his beloved Cherokee Nation as he served it faithfully for decades. This story of Elijah Hicks is written to resurrected his memory and to highlight his commitment to using his position of authority to bring peace to troubled nations.

Elijah Hicks’s headstone states he was born, June 21, 1797, in the old Cherokee Nation in the east. The son of devout Christian parents, his father was Charles Renautus Hicks, one of the first Cherokees to be educated in the English style by Moravian missionaries; his mother was Nancy Anna Felicitas Broom.

Elijah married, in 1823, Margaret Ross, sister of Principal Chief John Ross. To them were born at least six children – four of whom are also buried in Woodlawn Cemetery.

Many well-preserved primary sources remain to highlight Elijah Hicks’s historical contributions. While serving as clerk of the Cherokee National Committee and Council, 1822 – 1824, Mr. Hicks was responsible for recording the actions of the council’s financial affairs, and he signed, along with other leaders, countless resolutions recorded in Laws. The Cherokee Nation & C. September 11, 1808, to November 9, 1825. The underlying aim of these rulings was to organize a unified, civilized, and peaceful nation.

Yet, tension was building within the United States to remove the Cherokee from their eastern homelands. A letter to US President James Monroe (January 19th, 1824), signed by John Ross, George Lowrey, Major Ridge, and Elijah Hicks, requested the federal government intervene on behalf of the Cherokee Nation to stop the escalating pressure to relinquish Cherokee land east of the Mississippi and to halt the illegal intrusion by Georgian citizens upon their native soil. At age 28, Elijah Hicks was promoted to President of the National Committee (1826 to 1827). It was following this time that John Ross, Elijah Hicks, and others intensified legal efforts to convince the US Congress that the Indian Removal Act of May 28, 1830, was unjust. On August 1, 1832, Elijah Hicks became editor of the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper that published the progress of ongoing diplomatic efforts, until May 31, 1834, when Georgian authorities seized the press to stop the newspaper’s anti-removal influence on Native people.

Regrettably, in 1838, the United States insisted the Cherokee Nation remove to Indian Territory, exchanging its well-developed land with its improvements, in the east, for wilderness land in the west.

At age 41, Conductor Hicks piloted one of thirteen Cherokee detachments, made up of 858 souls (men, women, and children) in a caravan of 43 wagons and 344 riding horses, on their perilous, 126-days, “Tsa-La-Gi” (Trail of Tears) lasting from September 1, 1838, to January 4, 1839. Five births and 34 deaths were recorded when the company reached its Indian Territory destination.

Following removal, Elijah Hicks was one of 48 Cherokee leaders who signed the “Constitution and Laws of the Cherokee Nation, 1939,” designed to bring peace and unity to opposing factions within the Nation that had differing political, leadership, and cultural ideologies.

In his book, History of the Cherokee Indians…, historian Emmet Starr records, Elijah Hicks “settled on the California (trail) at the present site of Claremore, where he conducted a general store… [“doing a flourishing business with the Osages.” (Claremore Progress, 11-19-1909)]. He was elected a delegate to Washington in 1839 and 1843. Elected Clerk of the Cherokee Senate in 1845 and having been chosen as Senator from Saline District …, he was elected president of the Senate.”

Giving rare insight into this noteworthy man’s character, an Elijah Hicks journal is preserved in Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol. 13, No. 1 (March 1935). This account shares Mr. Hicks’s six-month (December 1845 – June 1846) peace-seeking mission as a representative of the Cherokee Nation to the “wild” lands of western Oklahoma, revealing the extreme cultural differences between his people and the native people of the plains.

Attending emissaries were Cherokees Elijah Hicks, William Shorey Coodey, and Jesse Chisholm; US Cherokee Indian agent Pierce M. Butler and Col. M.G. Lewis; Creeks Tuchabatchee Mico and Chilly McIntosh; Seminole Wild Cat (Cooacoochee); and others. Eventually culminating at Comanche Peak, in present-day Hood County, Texas, a nearly 500-mile journey south on the Texas Road for Elijah Hicks, the gathering included Kickapoo, Comanche, Wichita, Caddo, Ioni, Lipan, Tonkawa, Keechi, and Waco tribes. The objective of this peace treaty was to stop bloodshed, theft, and kidnapping between people of all races and to broadcast the news that Texas had become a US state and was therefore under the protection of the United States military.

At the conclaves, leaders of east and west smoked the pipe of peace and gave speeches. Elijah Hicks eloquently shared, “We only knew each other before by name, but now we have seen each and know and feel that we are friends. Our meeting does our hearts good, and gives it light as bright as the Sun now Shining on us.” Mr. Hicks sincerely hoped to keep and preserve these newly made friendships. Meetings were followed by dancing, singing, gourd rattling, and feasting well into the wee hours of the mornings.

The peace talks started at Comanche Peak and ended at Barnards Trading House, April 25, 1846, with the giving of gifts. These were only preliminary conversations with the tribes of the plains. Ten years later, all peace efforts were disrupted by the Civil War.

Elijah Hicks concluded his journal by writing, “The end is now come to go home. Is my wife and children alive? I pray heaven to protect me home, away, away, away… June 5th, 1846 – Arrived this evening after a long fatiguing journey by way of the Chickasaws & Creek nations through hot prairies, swimming rivers and creeks, but keeping excellent health.” Surely, with his safe return, there was much rejoicing among his wife and family. There would be other long, diplomatic trips to Washington City in the east before Elijah Hicks passed this life, ten years later, August 6, 1856, when his earthly remains were benevolently placed by his loved ones in Claremore’s cemetery.

What a privilege it is to discover the true nature of Elijah Hicks, statesman, diplomat, and peacemaker, through reading his detailed journal, archived letters, governmental documents, and the newspaper articles left to us from the distant past. One would feel him justified in holding a grudge for the many wrongs he suffered in his lifetime. Yet, instead, Elijah Hicks made the most of every opportunity afforded to seek peace and pursue it, bringing reconciliation and blessings to his people and others. By seeking instruction from peacemakers of the past, we can draw from their wisdom and learn from their experience and be reminded of how important it is to be peacemakers in our own unsettled times.