Claremore Daily Progress June 7, 2018 Rick Heaton Progress Correspondent

About the time Jackie Robinson was breaking the color barrier, the Claremore Clowns were starting their semi-pro baseball team.

At least in baseball circles, Robinson’s entry into the Major Leagues was a huge deal. It was hopefully the start of something big.

“It was quite a deal,” said local historian Gerome Riley. “He came in with the (Brooklyn) Dodgers. Branch Rickey (executive for the Dodgers) had heard of Jackie Robinson and his skill in baseball. And he hired him. Branch Rickey got a lot of flack when he came up there. Jackie Robinson got so many threats. A lot of people don’t understand, but I do. A lot of people don’t understand blacks, the way they act and the way they feel because they aren’t black. They haven’t been through the stuff we’ve been through and we’re still fighting. We’ve been fighting our whole lives for the rights that are supposed to be ours, but we don’t have them. We’re still fighting.”

“Before I started playing with them (Clowns) we had a team, a younger team, called the Hot Shots,” Kilpatrick said. “I remember when Gerome played and Henry Johnson was the catcher. I played for several years.”

Eventually, the races were integrated and whites and blacks played ball together, as it should be.

“A lot of guys from across the tracks came to play with us because they knew we were good,” Riley said. “It was a lot of fun. It wasn’t like we were getting paid, but we had a lot of fun.”

In the end, Jackie Robinson changed minds and hearts. It was the beginning of something special as far as race relations.

“Those teams did everything to them guys when Jackie Robinson was there,” Riley said. “But when Jackie Robinson got in there and got to playing and felt comfortable and got to running and stealing bases, they couldn’t hate him anymore. Then they started recruiting black players. You had to recognize it. Once you establish it, you can’t hold it back.”

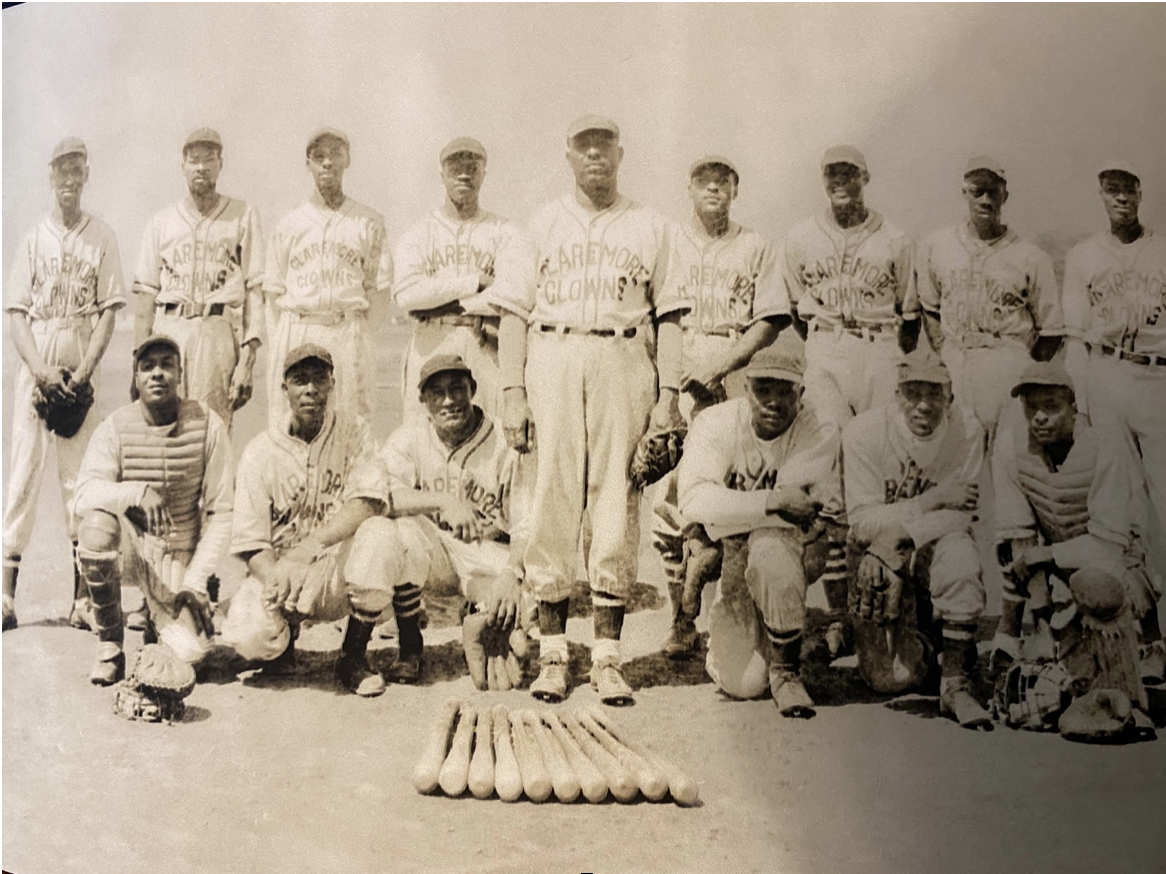

Robinson came up in 1947, the same year as the picture above of the Clowns. And this was a group of skilled players.

The team’s catcher, Mac Kilpatrick, played with a cigar stub under his catcher’s mask during games. It wasn’t lit, he just liked to chew on it.

His son, Mac Kilpatrick, Jr., was just a young boy at the time. He remembers being there.

“I remember being at the ball park,” he said. “We were out running down foul balls. You’d bring the ball back and get a bottle of pop. But I really don’t remember a whole lot. Back in those days, adults didn’t tell kids nothing.”

Most of what Kilpatrick knows about his father comes from those who knew him.

“His dad was a good catcher,” Riley said of Kilpatrick. “Mac was a good catcher. He wasn’t that good of a hitter, but he’d get those Texas leaguers. He was good at that. All of the guys on these teams, they played all positions.”

And they played all over the place. They played the T-Town Clowns from Tulsa. They played Bartlesville, Nowata, Siloam Springs, Ark., Prairie Grove, Ark., Joplin, Mo., and Salina to name a few.

“We’d go play in Salina and most of those guys were Native Americans and they loved to play ball,” Riley said. “We’d play one game and we’d get through and they’d want to play another as long as the sun was up. It was over around the lake and we’d go swimming. We just had a good time.”

The team was considered semi-pro. According to Riley, the team certainly wasn’t getting rich playing the game they loved. And the Jackie Robinson effect hadn’t trickled down by that point. The Clowns still had their struggles.

“They were treated like they were black,” Riley said. “But we never did have a lot of problems. During the times I was playing in 1950, 1951 and 1952, it was all segregated.”

During the season, baseball fans would pay a quarter or 50 cents to get into a game. The home team would take 60 percent of the gate, while the visitors grabbed 40 percent. Usually, it was about enough to pay for gas and maybe some food.

The Clowns played at a park on Oseuma Street in Claremore. And they were treated well by the town.

“We had a lot of outstanding players,” he said. “The main ball park was outside on the north side of town. It was a nice park. The city put lights and everything out there. The stands would be full. Sometimes when we went out of town, there would be more than that. We’d go all over the place. You name it.”

At the time, with Jackie Robinson just breaking the color barrier, it would take some time for black athletes to get their shot. Riley watched as his friend, Chelsea native and New York Yankees World Series MVP Ralph Terry, got his chance.

“I was born and raised in Chelsea,” Riley said. “I used to catch. I played third base and pitched. I played with Ralph Terry.”

But since Riley was forced to attend Lincoln School in Claremore and Terry was allowed to attend Chelsea High School, they didn’t play in high school together. Schools were still segregated at the time.

“Ralph used to come by the house, he lived about three blocks from me,” Riley recalls. “They always kept the blacks separate in any town you went to. Chelsea hadn’t integrated but they had a coach there. He let us play regardless. I admire him for that.”

Though the games weren’t affiliated with the school, Riley remembers catching him and another great Chelsea player, Galen Hudspeth.

“In the summertime, we’d go up to McSpadden park and play from sun up to sun down,” he said. “Ralph would pitch and I would be catching. He was a Yankees fans and I was a Cardinals fan. He said, ‘Riley, I’m going to play with the Yankees.’ And I told him, ‘You’ve got to be kidding.’ As time went on, the school integrated and I kept up with Ralph. He went into the Yankees farm club and as time passed, he was starting in the rotation.”

But the Clowns were the highest level many of the players would ever reach. The team lasted from 1946-58, then younger players tried to keep things going.

Also during that time, players like Satchel Page were playing in the Negro Leagues. Page pitched for the Kansas City Monarchs among other teams. Though it wasn’t the Major Leagues, players in the Negro Leagues were certainly talented enough to play there.

“They could have played professional baseball,” Riley said. “When I was playing up at Chelsea, I didn’t advance because times were different. I don’t ever brag on myself, but I used to play a lot of ball. Things were like they were. I was hard for you the way things were.”

But Riley did get some recognition from Terry, who after retiring from baseball, attended the local Field of Dreams Banquet and served as the keynote speaker. Kilpatrick was there.

“The Field of Dreams I went to, Ralph Terry was the guest speaker at the race track,” he said. “The one thing he said was there’s only one guy who could catch me coming up, and it was Gerome Riley.”

Kilpatrick followed in his father’s footsteps by playing baseball.